This year in LLVM (2025)

It’s 2026, so it’s time for my yearly summary blog post. I’m a bit late, but at least it’s still January! As usual, this summary is about my own work, and only covers the more significant / higher-level items.

Previous years: 2024, 2023, 2022

ptradd

I have been making slow progress on the ptradd migration over the last three years. The goal of this change is to move away from the type-based getelementptr (GEP) representation, towards a ptradd instruction, which just adds an integer offset to a pointer.

The state at the start of the year was that constant-offset GEP instructions were canonicalized to the form getelementptr i8, ptr %p, i64 OFFSET, which is equivalent to a ptradd.

The progress this year was to canonicalize all GEP instructions to have a single offset. For example, getelementptr [10 x i32], ptr %p, i64 %a, i64 %b gets split into two instructions now. This moves us closer to ptradd, which only accepts a single offset argument. However, the change is also independently useful, because it allows CSE of common GEP prefixes.

This work happened in multiple phases, first splitting multiple variable indices, then splitting off constant indices as well and finally removing leading zero indices.

As usual, the bulk of the work was not in the changes themselves, but in mitigating resulting regressions. Many transforms were extended to work on chains of GEPs rather than only a single one. Once again, this is also useful independently of the ptradd migration, as chained GEPs were already very common beforehand.

There are still some major remaining pieces of work to complete this migration. The first one is to decide whether we want ptradd to support a constant scaling factor, or require it to be represented using a separate multiplication. There are good arguments in favor of both options.

The second one is to move from mere canonicalization towards requiring the new form. This would probably involve first making IRBuilder emit it, and then actually preventing construction of the type-based form. That would be the point where we’d actually introduce the ptradd instruction.

ptrtoaddr

LLVM 22 introduces a new ptrtoaddr instruction. This is the outcome of a long discussion on the semantics of ptrtoint and pointer comparisons for CHERI architectures.

The semantics of ptrtoaddr are similar to ptrtoint, but differ in two respects:

- It does not expose the provenance of the pointer. In Rust terms, it corresponds to

addr()instead ofexpose_provenance(). - It returns only the address portion of the pointer. This matters for CHERI, where pointers also carry additional metadata bits.

A non-exposing way to convert a pointer into an integer is an important step towards figuring out LLVM’s provenance story. LLVM currently ignores the fact that ptrtoint has an (exposure) side-effect, and having a side-effect-free alternative is one of the prerequisites to actually taking this seriously. (The other is the byte type.)

The downside of having two instructions that do something similar but not quite the same is that it requires careful adjustment of existing optimizations to work on both forms, where possible. This is something I have been working on, and ptrtoaddr should now be supported in most of the important optimizations.

Lifetime intrinsics

LLVM represents stack allocations using alloca instructions. These are generally always placed inside the entry block, while the actual lifetime of the allocation is marked using lifetime.start and lifetime.end intrinsics. The primary purpose of these intrinsics is to enable stack coloring, which can place stack allocations that are not live at the same time at the same address, greatly reducing stack usage.

I have made two major changes to lifetime intrinsics: The first is to enforce that they are only used with allocas. Previously, it was possible to use them on arbitrary pointers, such as function arguments. This is incompatible with stack coloring, which requires that all lifetime markers for an allocation are visible – they can’t be hidden behind a function call.

Making this an IR validity requirement was helpful in uncovering quite a few cases where we ended up using lifetimes on non-allocas by mistake, as a result of optimization passes. Most commonly, the alloca was accidentally obscured by phi nodes.

The second change was to remove the size argument from lifetime intrinsics. In theory, this argument allowed you to control the lifetime of a subset of the allocation. In practice, this was never used, and stack coloring just ignored the argument. This was a smaller change in terms of IR semantics, but significantly larger in impact because it required updates to all code and tests involving lifetime intrinsics.

While these changes have resolved some issues with our handling of lifetimes, more problems (with store speculation and comparisons) remain. A core issue is that in the current representation, it’s not possible to efficiently determine whether an alloca is live at a given point, or whether the lifetime of two allocas can overlap. Fixing this requires more intrusive changes.

Capture tracking

Another piece of work that carried over from the previous year are improvements to capture tracking. I proposed this last year, but the majority of the implementation work happened this year.

The most important part of this proposal is that we now distinguish between capturing the address of a pointer, and its provenance. Many optimizations only care about the latter, because only provenance capture may result in non-analyzable memory effects.

The most significant changes to enable this were inference support, and updating alias analysis to only check for provenance captures and make use of read-only captures.

I’ve also extended this feature by adding !captures metadata on stores. This is intended to allow encoding that stores of non-mut references in Rust only capture read provenance, which is helpful to optimize around constructs like println!(), which capture via memory rather than function arguments. Whether we can actually do this depends on an open question in Rust’s aliasing model.

ABI

One of the biggest failures of LLVM as an abstraction across different target architectures is its handling of platform ABIs, in the sense of calling conventions (CC). A large part of the ABI handling has to be performed in the frontend, which currently means that every frontend with C FFI support has to reimplement complex and subtle ABI rules for all targets it supports.

To ameliorate this, I have proposed an ABI lowering library, which tells frontends how to correctly lower a given function signature that is provided using a separate ABI type system, which is richer than LLVM IR types, but much simpler than Clang QualTypes.

As part of GSoC, vortex73 has implemented a prototype for such a library. It demonstrates that the general approach works for the x86-64 SystemV ABI (one of the more complex ones), without significant overhead. For more information, see the accompanying blog post. Work to upstream this library is underway.

Another pain point is that information on type alignment is duplicated between Clang and LLVM (for layering reasons), and this information can get out of sync. This causes issues for frontends like Rust, which use the LLVM information. I’ve implemented some consistency checks to prevent more of these issues in the future. I’ve also removed the duplicate data layout definitions between Clang and LLVM.

I’ve also done some work to improve the backend side of things, by exposing the original, unlegalized argument type to CC lowering. This allowed cleaning up lots of target-specific hacks, like MIPS’ hardcoded list of fp128 libcalls.

ConstantInt assertions

The previous year, I introduced an assertion when constructing arbitrary-precision integers (APInts) from uint64_t, which ensures that the value actually is an N-bit signed/unsigned integer. The purpose of this assertion is to avoid miscompiles due to incorrectly specified signedness, which only manifests for large integers (with more than 64 bits).

Back then, I excluded the ConstantInt::get() constructor from this assertion to reduce the (already very large) scope of the work. I ended up regretting that when I hit a SelectOptimize miscompile, which is caused by precisely the problem this assertion is supposed to prevent.

That was enough motivation to extend the assertion to ConstantInt::get(). Once again, this required substantial work to fix existing issues (most of which were harmless, but I’ve caught at least two more miscompiles along the way).

Compilation-time

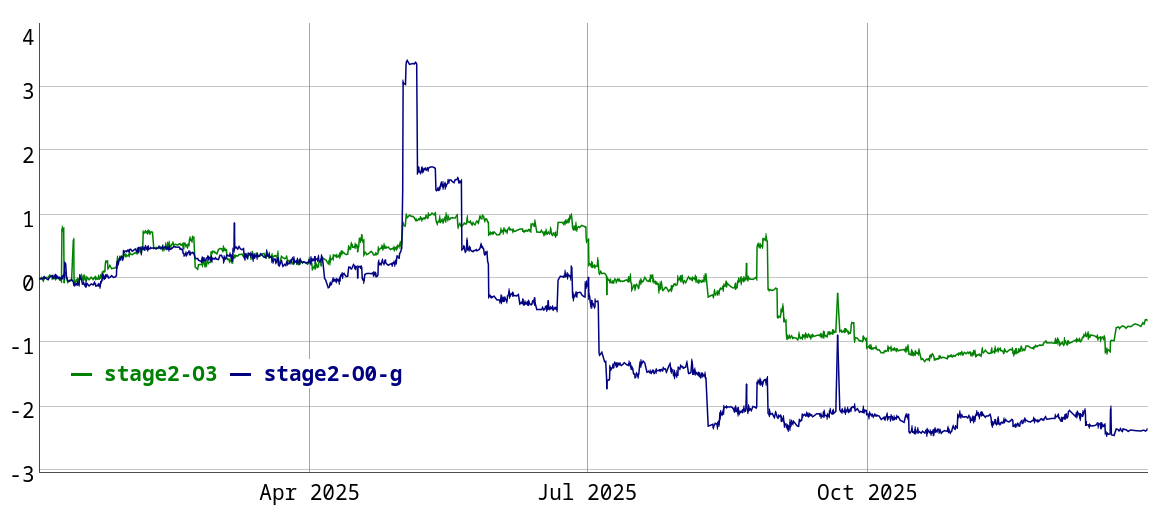

I have done little compile-time work this year, and there hasn’t been much activity from other people either. Here’s how compile-time developed over the course of 2025:

I have only included two configurations in the graph, because it is getting quite cluttered otherwise. Historically, I have only been tracking compile-times on x86, but have added two AArch64 configurations this year. An interesting takeaway from this is that compilation for AArch64 is around 10-20% slower, depending on configuration. For unoptimized builds, this is due to use of GlobalISel instead of FastISel. For optimized builds, use of alias analysis during codegen is a significant factor.

In terms of optimizations, I’ve implemented an improvement to SCCP worklist management (~0.25% improvement), which reduces the number of times instructions are visited during sparse conditional constant propagation. I’ve introduced a getBaseObjectSize() function (~0.35% improvement) to avoid use of expensive __builtin_object_size machinery where it is not needed. I’ve also specialized calculation of type allocation sizes (~0.25% improvement) to reduce redundant operations.

I’d also like to highlight two changes from other contributors. One was to optimize debug linetable emission, by avoiding the creation of unnecessary fragments. This improved debug builds by ~1%. Another was to change the representation of nested name specifiers in the Clang AST. I have no idea what this is doing, but it improved Clang build time by ~2.6%, so this has a big impact on C++ heavy projects.

I’m especially happy about the Clang change, as Clang is our main source of unmitigated compile-time regressions.

Optimizations

I don’t tend to do much direct optimization work: If the optimization does not require significant IR or infrastructure changes, we have plenty of other people who can work on it. But sometimes I can’t resist, so here are a couple of the more interesting optimizations I worked on.

I’ve implemented a store merge optimization, which combines multiple stores into a single larger store. LLVM already had some support for this in the backend, but it was rather hit and miss. The reason I worked on this is that someone on Reddit shared an example where Rust’s GCC backend actually produced better code than the LLVM backend, which is an injustice I just could not let stand.

I’ve enabled the use of PredicateInfo1 in non-inter-procedural SCCP (sparse conditional constant propagation). This enables reliable optimization based on constant ranges implied by branches and assumptions. Previously we only handled this during inter-procedural SCCP, which runs very early, and CVP (correlated value propagation), which is based on LVI (lazy value info) and has problems dealing with loops2. The main work here went into speeding up PredicateInfo, but we still had to eat a ~0.1% compile-time regression in the end.

Finally, I’ve implemented a pass to drop assumes that are unlikely to be useful anymore. This partially addresses a recurring problem where adding more assumes degrades optimization quality. This is just a starting point, we should likely be dropping assumes with various degrees of aggressiveness at multiple pipeline positions.

Rust

As usual, I’ve updated Rust to use LLVM 20 and then LLVM 21. Similar to all recent updates, this came with compile-time improvements (LLVM 20, LLVM 21).

Both updates went relatively smoothly. LLVM 21 ran into a BOLT instrumentation miscompile that defied local reproduction, but luckily an update of the host toolchain fixed it.

With these updates we were able to use a number of new LLVM features, some of which were added specifically for use by Rust.

The most significant is the use of read-only captures for non-mutable references. This lets LLVM know that not only can’t the function modify the memory, but it also can’t be modified through captured pointers after the call. This further increases the reliability of memory optimizations in Rust relative to C++.

Another is the use of the alloc-variant-zeroed attribute, which enables optimization of __rust_alloc + memset zero to __rust_alloc_zeroed. This ended up running into some LTO issues that required follow-up changes to fix attribute emission for allocator definitions.

We’re also marking by value arguments as dead_on_return now, and using getelementptr nuw for pointer arithmetic.

Packaging

The LLVM team at Red Hat has shared responsibility for packaging LLVM on Fedora, CentOS Stream, and RHEL. Most of the work happens as part of round-robin maintenance of daily3 snapshot builds. In theory, snapshot builds ensure that shipping a new major version is as simple as incrementing a version number. In practice, it never works out quite that easily.

In the previous year, we had already started using a monolithic build for the core llvm packages. This year, the mlir, polly, bolt, libcxx and flang builds were also merged into the monolithic build, which means that we only build libclc separately now. Additionally, the builds now use PGO. These improvements were made by my colleague kwk.

One change that I worked on, and which ended up as a big failure, was to increase the consistency between our main llvm package, and the llvmNN compatibility packages we provide for older versions. The compatibility packages install LLVM inside a prefixed path like /usr/lib64/llvmNN, while the main package is installed to the usual system paths. The idea was that we should always install to the prefixed path, and symlink from the system path. That way, the main package could be used the same as a compatibility package, avoiding the need for adjustments when switching between them.

The first issue this ran into is that RPM does not support replacing a directory with a symlink during upgrades. There are documented workarounds using pretrans scriptlets, but those don’t fully work.4 In the end we had to symlink individual files instead of symlinking entire directories.

The second issue only became apparent much later, after this change had already shipped: It was no longer possible to install the 32-bit and 64-bit packages of LLVM at the same time (known as the “multilib” configuration). While the prefixed path for both packages is different, they both install symlinks in the same system paths, and once again, RPM can’t deal with that. RPM has special “file color” support that lets 64-bit files win over 32-bit ones, but of course it only works for ELF files, not for symlinks.

I explored lots of options for fixing this, but everything ended up running into one missing RPM feature or another. In the end, I ended up inverting the symlink direction (making the version-prefixed paths point to the system path). The lesson learned here is that if you use RPM, you should avoid symlinks like the plague.

LLVM area team and project council

This year, LLVM adopted a new governance process, which includes elected area teams. Together with fhahn and arsenm, I have been elected to the LLVM area team. The LLVM area team holds a meeting every two weeks to discuss pending RFCs. (The meetings are public, but usually it’s just us three.)

Our approach has generally been hands-off. We have explicitly approved some RFCs where people expressed uncertainty, but usually our only involvement has been to provide additional comments on RFCs with insufficient engagement.

Unlike some other areas, I believe we had very few controversial proposals/discussions. One of them is an extensive discussion on floating-point min/max semantics, which has only been resolved recently. The other one was on delinearization challenges, but that was more a generic complaint than a specific proposal.

As chair of the LLVM area team, I also participate in the project council. This is kind of the opposite of the area team, in that nearly all topics that reach the project council are controversial – things like the AI policy, the mandatory pull request proposal, and the sframe upstreaming. While progress has been made, we haven’t reached final resolutions on many of these topics yet. The AI policy is now live though.

Other

Towards the end of the year, we formed the formal specification working group, which aims to close long standing correctness gaps in LLVM, especially relating to the provenance model. I’ve participated in various early discussions for this group and wrote up a draft provenance model for LLVM. The current focus of the group is the byte type.

I’ve deprecated the global context in the LLVM C API, a common footgun. I’ve changed the representation of alignment in masked memory intrinsics. I’ve simplified the in-memory blockaddress representation and proposed more significant changes for the future.

Last but not least, I reviewed approximately 2500 pull requests last year. Unfortunately, this is nowhere near enough to keep up with my review queue.

-

PredicateInfo performs SSA-renaming based on branch conditions and assumes. This results in something akin to SSI (static single information) form, and allows standard sparse dataflow propagation to make use of them. ↩

-

LVI is a shared analysis between JumpThreading and CVP. Because JumpThreading performs pervasive control-flow changes, it cannot preserve the dominator tree. As such, LVI also can’t use the dominator tree. This results in a purely recursive analysis, which conservatively aborts on cycles, even if there is a common dominating condition. ↩

-

In practice, we produce successful builds across all architectures and operating systems much less often than daily. Something always breaks. ↩

-

They solve the upgrade problem, but not the downgrade problem, so still fail rpmdeplint. And handling downgrades requires a change to previous versions of the package. ↩