This year in LLVM (2022)

Towards the end of last year, I switched from working on PHP at JetBrains, to working on LLVM at Red Hat. While it was already under discussion beforehand, this catalyzed the creation of the PHP foundation, which now pays multiple people to work on PHP. Special thanks for this go to Roman Pronskiy, who did most of the work to set up the foundation, and keeps it running ever since. Also a shout-out to Alexey Gopachenko, the unsung hero of PHP: As the PhpStorm team lead at the time, he drove JetBrains’ active investment in PHP core development and the community at large.

The PHP 8.2 release shipped a couple weeks ago with fairly little contribution from myself. I somehow still managed to make the most controversial change, which is the deprecation of dynamic properties. And with that out of the way, let me jump into the actual topic of this blog post, which is what I’ve been up to since then.

Opaque pointers

Historically, pointer types in LLVM carried an element type, for example i32*, <4 x i16>* or %struct*. In LLVM 15, these have been consolidated into an opaque ptr type.

The motivation for this change is simple: LLVM IR semantics say that the pointer element type carries no semantic meaning. You can take an i8* pointer, bitcast it into an i32* pointer and load an i32 value from it. Optimizations shouldn’t make use of the pointer element type – if they do, they are either suboptimal, or outright wrong. But of course, as long as the element type is available, we can hardly blame optimization authors for trying to make use of it.

In addition to that high-level motivation, there are also practical considerations: Opaque pointers remove the need for pointer bitcasts, which improves memory usage and compile-time. It also improves optimization power, because optimizations can no longer fail to handle bitcasts, or rely on element types as (often wildly inaccurate) optimization hints.

The opaque pointer migration started in 2015 and has been moving slowly for a long time, due to the sheer scope of the change. After I joined Red Hat, I spent a significant fraction of my time for many months on bringing this migration over the finishing line, with help from Arthur Eubanks. Some of the larger pieces of work were:

-

Migrating the Clang frontend to support opaque pointers. As the element type is no longer tracked by LLVM, frontends need to keep track of it separately. This work started with storing the element type in Address, which had this wonderful comment in it:

When IR pointer types lose their element type, we should simply store it in Address instead for the convenience of writing code.

This was followed by weeks of work migrating many hundreds of users of Address and related APIs to pass explicit element types. Simply.

-

Adding support for bitcode auto-upgrade (D118694, D119339, D119821, D120471). LLVM generally does not care about backwards-compatibility, with one exception: LLVM must be able to read bitcode produced by previous versions, auto-upgrading it as necessary.

This was a significant challenge with opaque pointers: While doing an upgrade to opaque pointers is nominally as simple as discarding the unneeded pointer element types, the problem is performing other auto-upgrades at the same time. For example, historically loads were of the form

load i32* %p, while now they explicitly specify the loaded type viaload i32, ptr %p. When thei32*gets upgraded toptr, we lose the necessary information to add the load type.This is solved by making the bitcode reader keep track of type IDs for all values, as well as which type IDs they contain as subtypes. For example, given a function pointer type like

void(i32*)*, a series of contained type ID lookups allows us to determine the pointer element type of the parameter. Unfortunately, this does add significant complexity to the reader. -

A number of optimization passes were using “structural reasoning”, where struct pointer element types were used to drive optimizations. These optimizations had to be rewritten essentially from scratch to perform offset-based reasoning instead: Analyze at which offsets and with which types the pointer is actually used. This is a requirement for supporting opaque pointers, but also increases optimization power, because it can support bitcasted pointers.

Examples of this include argument promotion, global SROA and global ctor evaluation.

-

The long tail of “everything else”. There were hundreds of places inspecting pointer element types. Removing some of them was just a matter of switching to a different API, while others needed more substantial work and/or IR changes.

Once we got to the point of no longer crashing during compilation, this also involved tracking down miscompiles caused by opaque pointers: These were almost always due to a no longer correct assumption that two instructions using the same pointer also operate on the same type. With opaque pointers, this requires an explicit check.

Opaque pointers were enabled by default for the LLVM 15 release,

with a big caveat: We did not convert all LLVM and Clang tests to use opaque pointers. For Clang,

most tests were modified to pass -no-opaque-pointers, while

LLVM tests auto-detect the opaque pointer mode based on what kind of pointer types are used in the

test.

Even with some automation, converting tests to use opaque pointers is very time consuming. There has been good progress on this, but the migration is not yet complete. We will only be able to drop typed pointer support once the test migration is done. I look forward to removing all that pesky pointer bitcasting code.

Opaque pointers have extensive migration documentation, and I also gave a talk at CGO-LLVM on the topic (slides, recording). See those resources for more information.

Constant expression removal

My next big project of the year was the removal of constant expressions. Historically, LLVM has supported a constant expression variant of nearly all instructions.

@g = external global i32

; Instruction

define ptr @test1() {

%res = getelementptr i32, ptr @g, i64 1

ret ptr %res

}

; Constant expression

define ptr @test2() {

ret ptr getelementptr (i32, ptr @g, i64 1)

}

Some notion of constant expressions is needed for global variable initializers:

@g = external global i32

@g_end = global ptr getelementptr (i32, ptr @g, i64 1)

Only a small handful of “relocatable expressions” can actually be used as initializers. These basically come down to adding an offset to a global and, depending on the object file format, computing the offset between two globals.

However, LLVM conflated this initializer concept with general constant folding and allowed (nearly) all instructions to also be used as constant expressions. This also included integer division instructions, which cause undefined behavior when dividing by zero.

The end result was that certain “trapping” constants were non-speculatable, which most code failed to account for, leading to miscompiles. In issue #49839 I tried to fix an end-to-end miscompile related to this issue, but every time I fixed a bug in one pass, a new variant of it appeared in another.

Ultimately, I came to the conclusion that the only way to fix this problem is by design: The notion of trapping constants has to be removed entirely. Incidentally, constant expressions also cause plenty of other issues, such as incorrect cost-modelling (treating complex expressions as being “free”), some bits of exponential behavior, as well as the need for code to deal with two different representations of the same thing. As such, the proposal was aimed more broadly at removing all non-relocatable constant expressions.

Once again, the main technical complexity of this change lies in bitcode auto-upgrade. Constant expressions that are no longer supported need to be expanded into instructions. This is done by decoding all constant expressions into a virtual representation first, which can then be materialized in different places. The notion of (formerly) trapping constants means that this expansion has to happen at exactly the right place, e.g. an expression in a phi node might require critical edge splitting. Once again, this adds some non-trivial complexity to the bitcode reader.

A complicating factor that I encountered here (though not for the first time) is uselistorder preservation. LLVM values maintain a list of uses, and in some cases the order of this list can impact optimization behavior. While LLVM does not preserve it by default, there is an optional mode (-preserve-bc-uselistorder) to retain it.

Uselistorder preservation works by having the bitcode writer “predict” the uselistorder that will result from plain bitcode reading, and then store a shuffle that will convert the predicted order into the actual one. Getting the uselistorder prediction correct when making major changes to bitcode reading is fairly tricky.

Once the base infrastructure was in place, it was possible to remove division expressions and with them the notion of trapping constants and their associated miscompiles.

I also removed a few more constant expressions, namely extractvalue, insertvalue, fadd, fsub, fmul, fdiv, frem and fneg. However, there are still quite a few expressions left, and I haven’t done recent work on this. Each removal requires significant effort to remove all users of the respective constant expression API. I expect I’ll come back to this on an as-needed basis.

Callbr representation

LLVM represents asm goto using the callbr terminator in IR. Historically, this made use of block addresses:

%res = callbr i32 asm "...", "=r,r,i"(i32 %x, ptr blockaddress(@foo, %indirect))

to label %fallthrough [label %indirect]

Block addresses were originally introduced for use by indirectbr, which is LLVM’s representation of computed goto. indirectbr stores a list of potential jump targets, while the actual jump target is passed in as a block address.

The use of block addresses imposes an unusual restrict on indirectbr: It’s successors cannot be updated. Doing so would also require updating blockaddresses corresponding to successors, and this is not generally possible. For example, consider unrolling an indirectbr: This would produce a clone of the instruction pointing to cloned blocks, and there is no sensible way to update blockaddress references (which of the blocks should they refer to?)

Many control-flow transforms want to update successors, and indirectbr is very rare, so this is a semi-regular source of assertion failures. The implementation of callbr originally adopted the same design, and as such inherited all its problems. For the asm goto use-case, this is unnecessarily restrictive, because all blockaddresses will be direct operands of callbr, and as such can be updated.

As such, I changed the callbr design to remove the blockaddress operands, and instead introduce a new asm constraint modifier !, which indicates that a certain asm operand should be taken from the callbr indirect label list, rather than the call arguments:

%res = callbr i32 asm "...", "=r,r,!i"(i32 %x))

to label %fallthrough [label %indirect]

This representation change both removes optimization limitations, and makes them more robust, because callbr can now be essentially treated like any other control-flow, without unusual restrictions. The one remaining restriction is that the callbr result can only be used on the fallthrough edge, but there is ongoing work to remove this limitation.

As a side note, I think there is an opportunity to improve the indirectbr situation by making blockaddress references not refer to a block, but rather to a certain indirectbr successor, along the lines of indirectbrsuccessor(some_indirectbr_identifier, 0). This would not allow cloning of indirectbr, but permit most other CFG transforms and critical edge splitting in particular.

Memory effect modelling

The last major IR change of the year was a revamp of memory effect modelling. Historically, LLVM specified memory effects of functions using a combination of two attributes families: readnone/readonly/writeonly specify what kind of access is allowed, and argmemonly/inaccessiblememonly/inaccessiblemem_or_argmemonly specify which locations can be accessed.

This modelling has two core problems: First, it does not allow specifying the read/write kind per location. For example, it’s not possible to precisely model a function that can read any memory but only write arguments. Second, it makes it hard/impossible to add new memory location kinds, because this would require an exponential number of attributes to encode different combinations.

The new representations uses a single memory(...) attribute, which is internally backed by the MemoryEffects class (formerly known as the FunctionModRefBehavior). The attribute specifies which access kind is allowed for each memory location. Examples are:

; Same access kind for all locations

declare void @foo(ptr %p) memory(none)

declare void @foo(ptr %p) memory(read)

declare void @foo(ptr %p) memory(write)

; Specific access kinds for specific locations

declare void @foo(ptr %p) memory(argmem: write)

declare void @foo(ptr %p) memory(inaccessiblemem: readwrite)

declare void @foo(ptr %p) memory(argmem: read, inaccessiblemem: write)

; Default access kind, plus specific access kind for some locations

declare void @foo(ptr %p) memory(read, argmem: readwrite)

declare void @foo(ptr %p) memory(readwrite, argmem: none, inaccessiblemem: none)

The new representation was implemented in a patch stack ending at this patch. This was another somewhat annoying change, in that it required updating many places working with memory attributes, and even more tests, in an atomic commit.

While the new representation already provides some benefits in itself (such as accurate materialization of inference results, and as such better optimization), a large part of the motivation for this change is the ability to track new memory locations in the future.

Currently, we only track arguments, inaccessible memory and “everything else”. The somewhat oxymoronic notion of inaccessible memory refers to memory that is not visible to the current module. Intrinsic side-effects are commonly modelled as a read and write of inaccessible memory.

This could be refined to, for example, separately consider accesses to global variables, as well as captured/escaped pointers. Furthermore, explicitly modelling thread identity as a memory location would properly address issues related to the fact that thread identity can change inside a coroutine function.

Allocator support

This was not my own proposal, but I was involved in the work, so I’ll mention it here as well. LLVM supports quite a few optimizations on memory allocation functions, such as removing unused allocations. Historically, these were based on a hardcoded list of allocator functions.

The allocator attributes proposal encodes the necessary information using attributes instead, which allows frontends (and in particular Rust) to teach LLVM about their custom allocation functions, without having to patch LLVM. Previously, Rust included such a patch in rustup-distributed binaries, but the same optimization was not available in distro-provided binaries.

We might as well use the Rust allocator functions as an example for how the new attributes look like:

declare noalias ptr @__rust_alloc(i64 %size, i64 allocalign %align)

allockind("alloc,uninitialized,aligned")

allocsize(0)

"alloc-family"="__rust_alloc"

declare noalias ptr @__rust_alloc_zeroed(i64 %size, i64 allocalign %align)

allockind("alloc,zeroed,aligned")

allocsize(0)

"alloc-family"="__rust_alloc"

declare noalias ptr @__rust_realloc(ptr allocptr %ptr, i64 %old_size, i64 allocalign %align, i64 %new_size)

allockind("realloc,uninitialized,aligned")

allocsize(3)

"alloc-family"="__rust_alloc"

declare void @__rust_dealloc(ptr allocptr %ptr, i64 %size, i64 %align)

allockind("free")

"alloc-family"="__rust_alloc"

There’s quite a few different attributes involved here! Here’s what they are for:

noaliason the return indicates that the allocator returns a pointer with fresh provenance. There is no (well-defined) way to read or write the allocated memory except by going through that pointer. (This is a pre-existing attribute.)allocsizeindicates the number of the argument that specifies the allocation size. The allocator must return a null pointer, or a pointer that is dereferenceable for that many bytes. (This is also a pre-existing attribute.)allocalignindicates the argument that specifies the allocation alignment. The allocator must return a pointer aligned to that value.allockindspecifies which kind of allocation function this is (alloc/realloc/free) and which properties it has.uninitializedmeans that the initial value of the allocation is uninitialized,zeroedmeans that it is zero.allocptrmarks the argument that is being reallocated/freed."alloc-family"marks the functions as being part of one family: Pairs of allocation functions can only be removed if they belong to the same family. Otherwise, we may run into issues when allocation functions are partially inlined.

My own involvement in this work (apart reviewing the patches) was in adjusting optimizations to query specific allocator properties they rely on, rather than performing a generic “is this an allocator?” check, which is not really compatible with the fine-grained attribute encoding.

For example, a lot of optimizations really only care about the provenance implications of allocators, and as such should be checking for the presence of a noalias return value, and nothing else.

We are not entirely clean on this front, mainly because there are a number of optimizations which are not, strictly speaking, correct.

Integer min/max intrinsics

Historically, LLVM has represented integer min/max operations as an icmp+select sequence. For example, a umin would be a < b ? a : b. This is known as the “select pattern flavor” (SPF) representation.

Representing min/max operations as icmp and select has the big advantage that all existing optimizations on icmp and select instructions automatically work on them.

It also has the big disadvantage that all existing optimizations work on them: We very much don’t want to break up canonical min/max patterns, to ensure that the backend can recognize and efficiently lower them. As such, there is a continuous tension between trying to optimize icmps and selects, while also trying to not break min/max patterns. The outcome has been many infinite transform loops.

One of the other motivations for moving away from this representation is that, thanks to the peculiar semantics of undef values, some common-sense properties do not hold in SPF representation. For example, min(x, 7) & 7 could not be legally folded into min(x, 7) if x is an undef value (proof). The reason is that the value of undef can be separately chosen in the icmp and select instructions (one of the reasons why we are moving away from undef).

Long story short, a few years ago the llvm.umin, llvm.umax, llvm.smin, llvm.smax and llvm.abs intrinsics were introduced. However, it took us quite a while to ensure that all optimizations on the SPF representation also work on the intrinsic representation. Last year, I addressed the final missing folds, and then enabled canonicalization from SPF to intrinsic representation.

Branch on poison

Moving on from IR representation, let’s talk about semantics instead! LLVM has a notion of poison values, which are essentially delayed undefined behavior. Immediate undefined behavior only occurs once the poison value is passed to certain operations. Where possible, we prefer to define IR semantics in terms of poison values, because this allows operations to be speculated (undefined behavior renders operations non-speculatable).

One of the operations that turns poison values into immediate undefined behavior are conditional branches. However, while this was already specified in the LLVM IR specification for a long time, we were aware of many optimizations that introduce new branches on poison. As such, we were not willing to actually exploit branch on poison UB except where it was grandfathered in.

These issues are usually easy to fix and tend to come in two flavors. First, when introducing new branches, the branch condition needs to be frozen:

%res = select i1 %c, i32 %x, i32 %y

; convert into

%c.fr = freeze i1 %c

br i1 %c.fr, label %if, label %else

if:

br label %join

else:

br label %join

join:

%res = phi i32 [ %x, %if ], [ %y, %else ]

Freeze converts the poison value in an arbitrary (but fixed) well-defined value, in this case either true or false. Inserting freeze is necessary here, due to the difference in poison semantics between select and br: Select on a poison condition returns poison, while branch on a poison condition is immediate undefined behavior. (A freeze is not needed when converting br to select, which is the much more common transform.)

The second case occurs when merging conditions, for example converting two separate branches into an and:

br i1 %c1, label %if1, label %else

if1:

br i1 %c2, label %if2, label %else

; convert into

%and = select i1 %c1, i1 %c2, i1 false

br i1 %and, label %if2, label %else

Converting this into %and = and i1 %c1, %c2 would be incorrect, because if %c1 == false and %c2 == poison, this would also make %and poison and cause immediate undefined behavior, which was not present in to the original program. Instead we create a “logical” and, which does not propagate poison from the second operand, if the first one is already false. There is also a logical or operation:

and i1 %c1, %c2 ; Bitwise And

select i1 %c1, i1 %c2, i1 false ; Logical And

or i1 %c1, %c2 ; Bitwise Or

select i1 %c1, i1 true, i1 %c2 ; Logical Or

Much to the chagrin of certain parts of the Rust community, the fact that it’s easy to “fix” is not enough: When it comes to largely theoretical miscompiles, the baseline expectation is that a reasonable effort is made to mitigate the optimization impact of the change. Just slapping freeze on everything is easy, but analyzing and mitigating the optimization regressions this results in requires a large amount of work.

In this case, work was required mainly in three areas. The first is scalar evolution (SCEV), which is the analysis framework for loop optimizations. If a loop has exactly two exits, one after %n iterations, and one after %m iterations, then the exit count of the loop is not %n umin %m, but rather %n umin_seq %m. The distinction is that if %n is zero, then a poison value from %m does not propagate. If the first exit exits on the first iteration, then the second condition will never get evaluated.

Before making that change, I had to implement a number of improvements to umin_seq analysis. For example, we can use poison implication reasoning to convert umin_seq into umin.

The second area is optimization of logical and/or. While we already did a substantial amount of work to support these operations throughout the optimization pipeline, I still ran into multiple optimization regressions related to them. The most important change here is probably to consolidate the logic for optimizing bitwise and logical and/or of icmps, which then allows us to enable reassociating folds, and makes it easy to spot and fix cases where handling for logical operations is missing.

Last but not least is freeze optimization. Analysis generally cannot look through freeze instructions, so we try push it upwards in the instruction chain. freeze (icmp X, 0) is essentially an opaque value, while icmp freeze(X), 0 can be analyzed and optimized. We were already mostly doing this, but were failing to push through freezes that are part of a recurrence. In this case, we want to move the freeze to the start value of the recurrence, rather than freezing the value on each loop iteration.

Additionally, if freeze %x is used, we want to make sure that all other uses of %x are also frozen. Nominally, this may seem like a an anti-optimization, because we’re replacing uses of %x with freeze %x. However, this is beneficial in practice, because it allows transforms based on value identity to work. If a fold is looking for some value V in two different places, we can’t have one of those be %x and the other freeze %x.

With all issues fixed and optimization regressions addressed, we can finally rely on the specified semantics. The most important change is to exploit this to prove that a certain value cannot be poison without causing UB. This is particularly important for SCEV, and part of the reason why I started working on this in the first place.

Rust

As usual, I performed the upgrades to LLVM 14 and LLVM 15 in Rust. Since Google started testing Rust HEAD against LLVM HEAD, these upgrades have become somewhat simpler, because any necessary changes to LLVM bindings have already happened. Despite that, these updates never just work, because of issues on non-x86 or non-Linux platforms.

For example, LLVM 14 broke ABI for certain builtins on Win64. LLVM 15 exposed some issues in rustc’s management of LLVM worker threads, and changed handling of atomics on thumbv6 in a way that required the addition of a new target feature to support Rust’s desired semantics.

Usually, a good part of the work is to just get LLVM building on all CI images. To be compatible with old glibc and kernel versions, these often use very old compiler toolchains, which LLVM supports only theory, but not in fact. LLVM 16 raises the minimum requirement to GCC 7.1, and Josh Stone has been doing great work getting rustc ready for this change, including a raise in baseline requirements for linux-gnu targets, which is necessary to get sufficiently recent cross-compilation toolchains.

Apart from LLVM upgrades, I also try to address any (LLVM-related) miscompiles or assertion failures that get reported against rustc, and look into optimization problems. Some new optimizations targeted at Rust are:

- Support for peeling loops with non-latch exits. This was motivated by an optimization problem with iter().skip(), but should fix a number other performance issues with exterior iteration over iterator adaptors as well.

- Support for load-only scalar promotion in the presence of aliasing loads, motivated by an optimization problem with array::IntoIter.

- Improved support for pushing operations across phi nodes, motivated by an optimization issue with iter().fold(). This was my most cursed revision: It went through five revert cycles before it stuck.

- Improved support for removing phi nodes of single-iteration loops and simplifying the result. This was motived by an optimization issue with slice::reverse().

There’s certainly a pattern here: optimizing iterators is hard. Apart from that, there’s some new bounds/overflow check optimizations (e.g. with.overflow support in IPSCCP), as well as minor improvements to memcpy elimination (e.g. support for moving lifetime intrinsics, addressing regressions from MIR inlining). Iterators, bounds checks and memcpy are the trifecta of Rust optimization.

Fedora

While I work at Red Hat, I haven’t actually done any work directly on RHEL yet. I did package LLVM 15 for Fedora 37, which then serves as the template for the RHEL packages. This was new to me, as I haven’t done any packaging work before.

Incidentally, both LLVM and Fedora release major versions twice a year, so each version of Fedora comes with a new LLVM version. This starts with a self-contained change proposal. Once release candidates are available, these get built in COPR, and once the GA release is available, the Fedora RPM repositories get updated, and builds are produced inside a side-tag, which is then merged by bodhi.

A side-tag is basically a temporary fork of Fedora, which allows building multiple packages, and making sure these only get merged together. If we update to llvm-15.0.0, we also need to update to clang-15.0.0 at the same time. Fedora actually packages 16 different LLVM subprojects, so these all get pushed out as part of the same update.

Because the LLVM and Fedora release cycles are somewhat misaligned, the LLVM update goes in rather late (after the Fedora beta release), long after the package mass-rebuild. To avoid the need to rebuild all packages against the new LLVM version, compatibility packages (like llvm14) are provided. These provide the libraries needed by already built packages, and can be used to produce new builds if a rebuild against the new LLVM version is not feasible.

Updating LLVM in Fedora was a good bit more work than I expected. Part of this comes down to the fact that Fedora uses standalone builds, where each LLVM subproject is built separately (and links against libLLVM.so etc), while the standard LLVM build configuration is a monolithic build that produces everything from LLVM over clang to libcxx in one go. As a non-default build configuration, LLVM developers always find new and exciting ways to break standalone builds.

Compile-time

I maintain the LLVM compile-time tracker (see original blog post) and make sure that any significant compile-time regressions at least get an investigation. In many cases just informing the patch author is sufficient, and they will work on mitigating the impact themselves.

Significant regressions start at around 0.1%. The background to keep in mind here is that individual optimization passes often only take up a fraction of total compile-time, so an end-to-end regression of 0.1% is often a large regression in a single pass. It’s also quite common though, that regressions occur due to second order effects – for example, an optimization pushes a function over an inlining threshold, and that has major impact down the line. Such cases are generally considered uninteresting.

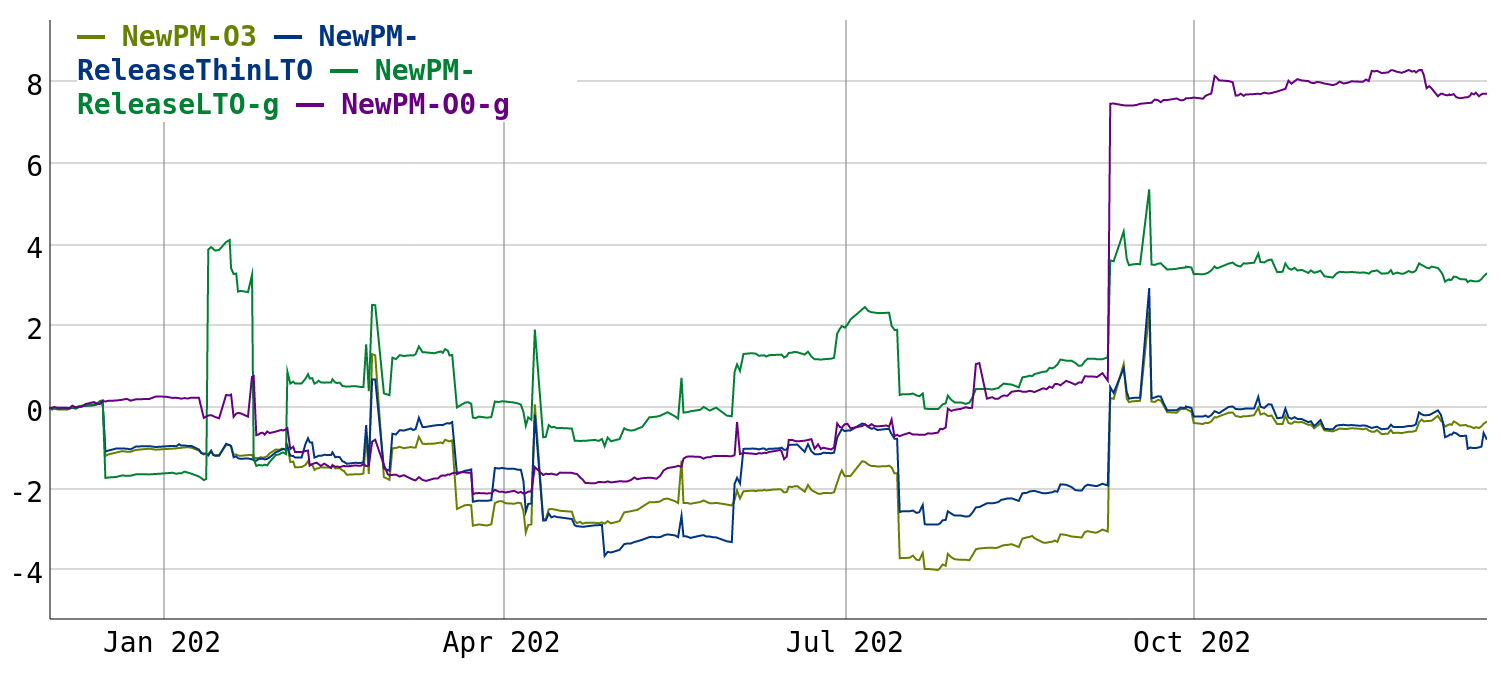

I recently added support for showing long-term compile-time changes, which look as follows since December 2021 (in percent since start):

I think this is the first time in quite a few releases where we end up with an overall regression. However, the situation is not quite as bad as it looks.

In particular, the large regression on the right is due to enabling C++17 by default. The close to two times slowdown in 7zip O0 builds comes down to STL headers becoming 2-3 times as large in C++17.

While this is sad, and I had to edit out some choice words on the C++ standardization committee (I hear that this gets even worse in C++20), at least this does not affect non-clang compilers (e.g. Rust) and C code.

The large regression in optimized debug builds (green line) on the left is due to more precise debuginfo variable location tracking in the backend getting enabled. This originally landed with a 6% geomean regression, but after work from both the patch author and myself, the regression was reduced to 2% when the change was relanded.

A big win in this period was a 2% improvement from not rerunning the function simplification pipeline on unchanged functions when reprocessing an SCC (strongly connected component) in the call graph.

One of my own optimizations leading to an 0.5% improvement was to support lazy use optimization in MemorySSA, which improved EarlyCSE performance.

What’s next?

With the opaque pointer migration finished, I’m only aware of one remaining major design issue in LLVM, which is the getelementptr instruction. While it ultimately just adds an offset to a pointer, it is specified in a type-based/structural way. Here are three ways to write the same getelementptr instruction:

%struct = type { i32, { i32, { [2 x i32] } } }

%ptr = getelementptr %struct, ptr %base, i64 1, i32 1, i32 1, i32 0, i64 1

%ptr = getelementptr i32, ptr %base, i64 7

%ptr = getelementptr i8, ptr %base, i64 28

However, while these are equivalent, optimizations have to go out of their way to treat them as such. Many GEP optimizations don’t bother and will only handle cases where the source element type (the first argument) is the same.

The situation here has become slightly worse with opaque pointers, because typed pointers at least provided some constraints on source/result pointer types and thus resulted in more consistent type use.

Ultimately though, the current representation is just bad, because it is completely divorced from the actual semantics of the instruction. A better representation would be an instruction that adds an offset to a pointer:

%ptr = ptradd ptr %base, i64 28

This would make many optimizations that work with address calculations much simpler, more reliable, and also faster (an embarrassingly large amount of time is spent converting GEP indices into offsets).

I have some hope that doing this change will be significantly simpler than the opaque pointer migration, mainly because we can both make getelementptr IRBuilder APIs emit ptradd instead, and pretend that ptradd is an i8 GEP, which will allow many things to work without changes. Of course, it would still be quite a complex change, and require another set of massive test updates.

On a different note, an area that deserves much more investment than it gets is compile-time. In the past year, my compile-time work was mostly focussed on mitigating regressions, not so much on improving things. I would like to start working on this more actively again. I think there is a lot of value in reducing compile-times, probably more than in adding increasingly low-impact optimizations.

I know that I’m not great at making long term plans, so I’ll leave it at those two items. Usually, things just turn up along the way. And in between, there are always miscompiles and assertion failures to fix, even though those don’t make for nice blog posts.

As a final note, I’ll mention that I’ve recently written a blog post on contributing to LLVM. It may be helpful if you want to start working on LLVM as well :)